Rebecca and Katy Beinart: Artist of the Month: March 2013

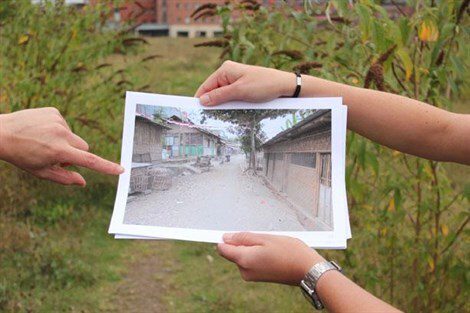

Katy & Rebecca Beinart, Bread & Salt, 2012. Photographed by William Beinart

We interview sisters Rebecca and Katy Beinart about collaborative working, their fascinating family history and involving the public in their projects.

Ruth Wilbur: What are you both currently working on?

Katy Beinart: I have just finished a residency/project in Brixton called The Anchor and Magnet', 2013, which was a collaboration with artists Barby Asante and Kate Theophilus and forms part of my PhD. We were based in a railway arch near Brixton market and collected people’s memories of the area as well as engaging in current debates around public space and regeneration. We put on a conference/symposium called The Brixton Exchange a few weeks ago which brought together artists, academics, residents and policymakers and I made a series of drawings of stories which became a newspaper pullout, distributed around Brixton.

Rebecca Beinart: I'm currently working on the Wasteland Twinning project in Nottingham, along with collaborators Mathew Trivett and David Bell. Right now we're mid-way through a programme of public events where we've invited guest speakers to help us interrogate some of the questions coming up in our research and practice around urban wastelands and art in public places.

RW: How was the Wasteland Twinning Network setup? Can you tell us a little about this, Rebecca?

RB: The Wasteland Twinning Network was set up by a group of artists in Berlin and now includes 14 sites around the globe. The simple idea of twinning wasteland sites raises many questions about the function of these pieces of land in cities, not least why we name them 'waste', and what their value might be beyond capital. The network provides a cross-disciplinary research platform to explore these questions, through arts practice, experimentation, conversation and writing.

I've been working as part of a collective in Nottingham looking at a specific site, and sharing or testing ideas through the wider network. We've been taking a playful approach to uncovering histories and diverse visions for the future of this area, including hosting a rounders' match on the site, amplifying one of its existing uses as a recreation ground. We've unofficially 'twinned' our wasteland with a site in Yogyakarta in Indonesia and we're hoping to work with our partners over there to continue exploring these two pieces of land with the communities who use them.

RW: You both regularly collaborate on projects together. What's it like working together so closely when you are sisters?

KB: Our collaboration grew out of the fact that we'd always be on the phone talking about what we were doing and one of us would say 'oh, I just read about such and such' and the other would say 'oh strange, I was just looking at that too', so we realised we were somehow in tune and, whether we work together or apart, we often seem to end up in the same or similar places of interest. Becca's choice to study art, in part, led to me becoming an artist after my own training as an architect.

RB: Yes, working together closely as sisters is very rich and challenging! We do offer alternative perspectives – we have different approaches and processes to making work. At our best we are able to spark one another's imaginations in a way that rarely happens with anyone else, but we can also slip into a classic sibling relationship - we've had to learn about the intensity of working together, and when we need to take a break.

RW: You both work on projects which involve participation and interventions in public places. Have there been interesting reactions to your work?

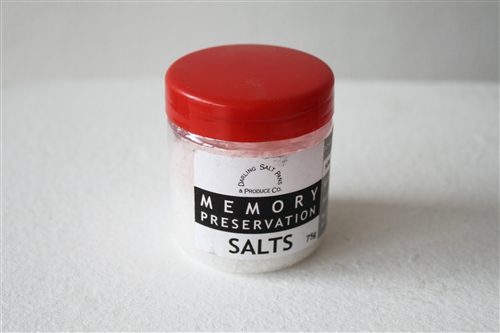

KB: When we ran our market stall in 2011 in Brixton Market and traded salt for stories (resulting in the work 'Memory Preservation Salts' (2011)), we got mixed reactions. Some people questioned our validity in taking on that role but that sparked really interesting conversations and debates about the rights and wrongs of history, who tells it and about the complex nature of heritage. Funnily enough our great-uncle Dave was a market trader there but I don't know what he would have thought of what we were doing, as he sold handbags! The project also raised a lot of questions for me about the subjective role of the artist/researcher and this has become a major thread of my PhD.

RB: Every person we spoke to in the market over that month had a fascinating story to tell. One of the things I found most interesting was the way that some people challenged us – and made assumptions about our identity and history. Talking about family history and personal migrations brought out some really big and difficult political histories – making us realise that we all have links to colonialism, slavery, wars. There's a choice about the stories we keep alive. Although we like to tell stories about our ancestors who were persecuted or heroic, we could equally tell stories of ancestors who were the opposite.

RW: You are both working together on a project called 'Origination' which investigates your genealogy. What surprises have you learned about your ancestry?

KB: I think the more you delve, the more you realise how difficult it is to really know your ancestors, but we've filled in a lot more detail about who they were, where they lived, etc. Finding the salt pans where Woolf Beinart worked was amazing. We also found out that a distant ancestor of ours, Rabbi Moishe Meisels, was a translator during Napoleon's war on Russia for the French High Command. He was asked to associate with the French military officials, to attain a position in their service, and to convey all that he learned to the commanders of the Russian army. After Moshe saved the Russian arms arsenal in Vilnius by alerting the Russian commander in charge, Napoleon stormed into the meeting room and pointed at him: " 'And who is this stranger?!' he said. 'You are a spy for Russia!'

RW: This is one of several projects you have worked on looking at ancestry, memory and family history. What do you think looking back tells you about the present?

RB: I think we both have a fascination with history – perhaps because our parents are historians. But I think that we also share an interest in public space and power – how the past shapes places, and people's relationships and freedoms.

KB: Hilary Mantel says this really nice thing about seeing ghosts only if you look out of the corner of your eyes, not directly - I feel that the past is always with us, only you can’t call it up to order and it’s when you’re not looking that it comes to play. Perhaps looking back tells you about what still needs to be resolved in the present.

RW: Katy, you originally trained as an architect and are in the middle of a PhD in Architectural Design at UCL. How does your background in architecture inform your practice? What are some of the challenges involved in creating work for public places?

KB: I think that my background has been a huge influence in the way I practise as an artist. Although I have moved away from designing buildings, I would say that the aspect of site is very important in my work and I use some architectural methodologies like mapping and technical drawing in the production of artworks.

It has also led to my interest in making work for public places and in understanding and engaging with the identity of places. When I was doing my master's, I got interested in what Ed Soja calls 'the socio-spatial dialectic' - how people and space/environment form each other and this is really at the root of my PhD project and most of my artworks. My PhD in Architectural Design explores this and is actually 'between' art and architecture.

RW: What was the last exhibition that you saw that made an impression on you and why?

KB: Most recently, Becca and I went to see the Suzanne Lacy piece Silver Action at the Tate. Our mum was in it so that made it especially moving. I found it very powerful partly because it is pretty rare to see a gathering of older women taking over a public place and also because the women's testimonies were so strong. They related a lot of challenges and hardship with no self-pity and described how they'd become activists. It also made me feel sad because our grandmother Margaret died last year and she was a lifelong activist and I felt like she should have been there too.

Interview by Ruth Wilbur, March 2013

Artists

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.