Barriers and Ethnic Representation

Commissioned by Axis as part of the 'Artist Exploitation' series in January 2024

Like many children of post war immigrants, I grew up in a cramped flat, ridden with moths and mould, in the middle of an ultra-urban area in Newcastle upon Tyne. My parents had lost their home due to the Partition in 1947 and came to find a better life in the UK. I was always drawing from a young age, sometimes on the peeling wallpaper, sometimes with stones on the pavement outside, as a means of escapism. My artwork became my hope, dreams and aspirations.

So believing I could grow up to work in the arts I went to study Photography and Film at Edinburgh Napier University in 2009. Unfortunately, despite Edinburgh being a cultural hotspot and capital city, there were no people of colour as lecturers on the course. In fact, the only leading experts we were referred to and who came to lectures as guest speakers were all older white men. Previously, in school my art teachers had also been white, a statistic which is common in the UK. In 2017, the Department for Education recorded that children in UK schools—of whom 31% were categorised as "minority ethnic"—were introduced to visual art by teachers who were 94% white. The structure of the degree I obtained, with its institutionalised curriculum, had no information in regards to financial or business acumen either.

These racial barriers and gatekeeping of knowledge made the route into a sustained practice increasingly difficult. Alongside this, shooting for exposure became normalised. I worked for free trying to build my client base, from NCJ Media, events and Asian wedding photography. By 2013 I had lost all hope of building my practice in the North East of England and resorted to working in a depressing call centre.

After a mental breakdown, I took an unconventional route into illustration some years later. My artwork exploring my South Asian culture ultimately rescued my poor mental health. However, my meandering across this route has really been the result of familial barriers. My ethnic background is questioned with ‘Where are you really from?’ With my Indian matchbox work that explores the North East of England, I am then asked to create them for free. There is a clear disregard of worth in these conversations. I think this fact is often overlooked as the arts and creative industries have a reputation that seems to exclude them from being seen as “real life jobs”. Many people view these creative careers as hobbies, or a side-line for a ‘real’ career and it is precisely this lack of respect for artists that is not only narrowing the industry, but also driving talented and gifted individuals away from their true passions because they cannot afford to sustain a livelihood on unpaid work.

Cultural appropriation is also a rife form of exploitation. This is when a member of the dominant culture — an insider — takes from a culture that has historically been and is still treated as subordinate, and profiting from it at that culture’s expense. Profit is key to exploitation. There are examples of casual cultural exploitation such as Indian matchbox art being sold without credit or context e.g. 'Flamboyant Matches’ by Archivist Gallery, with cherry-picked historical images. This loss of culture for marginalised people seems to be common ground in the UK’s consumerism.

As a brown-skinned woman who can speak four languages, I am aware of the lack of access to diverse arts in the North East of England. However, when working with some community centres in lower socio-economic areas, I have been alarmed by the differences of artist’s pay in relation to post codes. For example the Artists Union set a standard of pay, and some centres will pay half this amount as they don’t have the funds to pay the fair wage. This moral dilemma is concerning for artists who wish to make a difference, especially in the charity sector but who must then be penalised for working on the front lines. Considering the time it takes to write an application form, apply for funding, meetings, travel, and then tax it ultimately means the creatives are underpaid. For disabled artists who require access payments this can be worse, as the access is unavailable.

Ultimately, I hope that in the future less exploitation occurs. This can only be remedied through a fairer method that starts in a more diverse, prepared and updated education system.

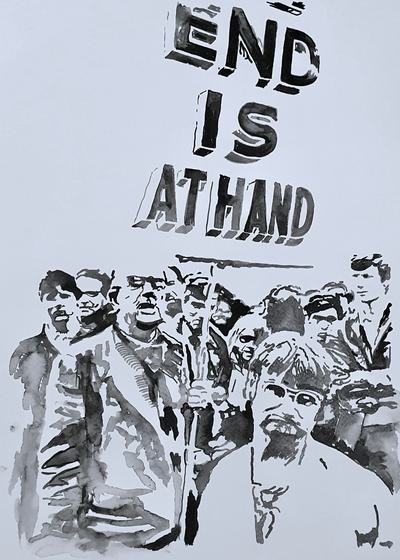

Unfortunately, the voices of groups who experience oppression and discrimination remain underrepresented in the arts sector.

References

British Institute of International and Comparative Law, Camila Adach, and Anna Khalfaoui. 2011. “The Human Right to Access and Enjoy Cultural Heritage in the United Kingdom.” Workshop Report, (March).

Gareth Harris. 2021. “How racist is UK art education? A new report aims to find out.” The Art Newspaper. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/03/15/how-racist-is-uk-art-education-a-new-report-aims-to-find-out.

“South Asians.” 2022. Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/minorities/south-asians/

Rogers, R.A. 2006. From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation. Communication Theory, 16: 474-503.

Sofia Barton March 2024

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.