The Price of Everything

by Alistair Gentry

Commissioned by Axis as part of the 'Artist Exploitation' series in January 2024

Imagine that every time you wanted to leave the house, there was some kind of meter on the door that would only let you out if you put cash or your debit card in it and paid. It’s not for anything in particular; the device’s only purpose is to extract money from you every time you go out. If you’re disabled this will be less of a leap into a sci fi dystopia than it would be for other people, because it’s more or less the situation that the 22% of the UK population who are disabled live in every day.

I’m not a fan of the term itself, but the so-called “‘crip tax”’ is a useful shorthand for all the extra costs of being disabled, D/deaf, or living with a long term mental or physical illness. We’re talking about obvious things like needing to get a taxi because the place you need to be isn’t served by public transport, or it is but you can’t physically get on the bus or see the bus stop. Maybe you need somebody to drive you all the way home because your meeting ran a bit late and now there’s no way you’re making it to the train station, in and out of four different lifts and onto the platform in time for the one accessible train that runs every three hours. In addition to crip tax there’s crip time too; the additional time and energy it sometimes takes to do the simplest things when you’re ill or disabled, from putting on your shoes to making your way past all the mundane things on the average street that become obstacles when you’re disabled. It can also be less obvious things that somebody needs for their comfort and dignity, things that non-disabled people probably don’t (and don’t want to) think about. The one expensive brand and model of phone whose screen you can actually see and interact with. I could go on for a really long time.

The disability charity Scope more politely calls this additional imposition on already disabled people’s time and capacity the Disability Price Tag. Using the latest figures available from 2019 their research showed that “‘on average, disabled households (with at least one disabled adult or child) need an additional £975 a month to have the same standard of living as non-disabled households.”’[1] Adjusted for the UK’s rampant inflation over 2022-2023, it’s £1,122 a month. This already takes into account and is therefore on top of disability support like Personal Independence Payment (PIP). As with Access to Work and other schemes supposedly designed to help, PIP is hellish to even attain in the first place, with tortuous, demeaning and humiliating systems for “‘proving”’ you have genuine need. And their targets are always more important than your need anyway. Many disabled people who do receive this hard-won help live in abject fear of it being taken away if they start earning “‘too much”’ (sic) money. Because, you know, being disabled or ill is such fun that everyone would want to get some of that action if they could. Without this extra support it obviously costs even more to be disabled and then you’re contemplating genuine destitution if not death itself. Before we even got to Brexit, Boris Johnson’s “‘let the bodies pile high”’ period of coronavirus mismanagement, and the cost of living crisis which is actually yet another greed of capital crisis, in 2021 the British Medical Journal calculated that the UK government’s austerity measures had already led to the “‘excess”’ – i.e. untimely and unexpected – deaths of 57,550 people between 2010 and 2015 due to cuts in social care, public health, and healthcare spending, and somebody dying from lack of these things is most likely elderly, ill or disabled.[2] According to the Office for National Statistics, in England and Wales at the height of the COVID pandemic between March 2020 and December 2022 there were 167,356 excess deaths. Deaths of people in their own homes were 29.1% above average.[3] Again, many of these were disabled people and people with existing long term health conditions who were either killed directly by coronavirus, or from being unable to access routine healthcare, an ambulance, or a hospital bed in lockdown.

So how does this relate to artists and the arts? I’m sure many readers will be well aware that low or no pay is a pervasive problem in the arts, so we’re all already behind. There are a few flagships apparently regarded as too big to fail; witness the English National Opera’s successful hoisting of the Arts Council England by their own petard after calling the latter’s bluff when ENO were removed from the national portfolio.[4] Most arts organisations, however, run on skeleton crews of overworked individuals who are often formerly or concurrently underpaid artists themselves. Pay has historically been poor for most in the arts. It has also spectacularly failed to keep up with economic inflation and rising wages in other sectors, many of which themselves have failed to take account of the increasingly steep cost of living. Most people in the UK in mid-level jobs like arts administration would be earning at least as much as a train driver if our governments cared and if more people bothered to join their unions. A train driver earns on average £57,593 a year, in case you were wondering, and yes, I am in full solidarity with their strikes to protect their pay and secure better conditions.[5]

Furthermore, the mushrooming of arts administration and other ancillary jobs in the arts sector has not been accompanied by a similar fertility in the opportunities and rewards for actual artists. , Qquite the contrary in fact. It’s probably still as hard as ever to be a practising artist in any kind of sustained and sustainable way. As a sometime- arts administrator I speak from experience when I say that many of these overworked roles are still basically what anthropologist David Graeber in his essential eponymous book calls Bullshit Jobs[6] specifically “‘Duct Tapers,”’ i.e. jobs that only exist because the system is broken and somebody needs to hold everything together somehow because the system ain’t getting fixed any time soon. The relatively recent adoption of any form of guidance on pay structure for artists only came through sustained grassroots campaigning over the last decade or so including but not limited to a-n’s Paying Artists Campaign[7], which I worked on, the formation of an English artists’ union, and the vocal efforts and meticulous research of independent individuals like Susan Jones[8]. Arts Council England and many other organisations do now point to union pay rates or the guidance of membership groups. It’s worth noting that the likes of ACE and the other national funders, who one would think should be leading on this, were explicitly forbidden many decades ago from publishing their own expectations of fair pay for artists on the grounds that it was “‘anti-competitive.”’ By a previous Tory government, obviously.

Let’s bring this back to disabled people again. Even five years ago we didn’t see the kind of awareness that we do as of early 2024 around disability and access. It’s great that more employers in the sector and commissioners of artists are being more thoughtful about inclusive language and interaction. I wonder, though, if this really changes anything if there’s no extra money involved as well. There are ever-increasing swathes of society who simply can’t afford to be in creative work because they don’t have the ‘Bank of Mum and Dad’ to withdraw from, or they’re not married to someone who actually does get paid. So if it costs me an extra £1,122 a month simply to exist compared to an otherwise similar non-disabled artist, how does this square with a commission still offering the same £1,500 that was being offered twenty years ago when there was never a disabled person in the building? Or indeed with a more general sense of fairness and equity?

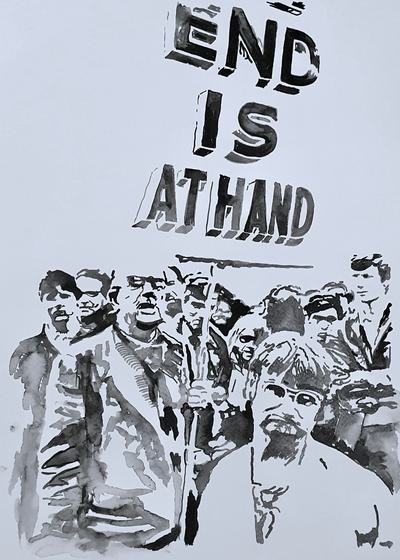

Worse still, a disabled artist might even be scared of getting paid too much, in case it screws up the state support they need to get medication, keep the care assistant they need, be able to leave the house now and then, or whatever it may be. In order for them to take that risk you need to be paying danger money in case the worst happens. All of the above makes offering to let people submit a video to apply instead of typing, saying you welcome neurodivergent people or whacking a BSL interpreter into every public event whether they're needed or not, for example, seem pretty hollow and performative not to mention conveniently cheap and apolitical. What the arts sector really needs, as with society as a whole, is a radical realignment of social and financial priorities. Start by paying a fair living wage to everyone who works in the arts, including artists. Eliminate bullshit jobs and give the money to artists instead because there’s no art without artists. Then we’ll move on to a universal basic income that puts a permanent floor under every single person so there can be no question of their needs for housing, food, education, healthcare and fundamental human dignity being met. Study after study shows that marginalised and minoritised people respond more than anything to the cash directly in their accounts and letting them decide how they spend it.[9,10] What we have at the moment, in the arts and in our country, is a rotten, ragged safety net that sometimes snares and strangles the people it’s meant to support while letting many others just fall straight through when they jump, or are pushed.

Citations

[1] Disability Price Tag 2023: the extra cost of disability, Scope, 2023, accessed 22 December 2023

[2] UK ‘austerity’ since 2010 linked to tens of thousands more deaths than expected, British Medical Journal, 14 October 2021, accessed 22 December 2023

Note the BMJ’s scare quotes around “‘austerity,”’ acknowledging this as an ideological project and political choice rather than an unavoidable necessity. “‘Excess deaths”’ sounds emotive but it’s a technical term to signify deaths above those that would be statistically and historically expected among a similar cohort of people during the same time of year.

[3] Fred Barton, Rebecca Smith, Alex Cooke, Excess deaths in England and Wales: March 2020 to December 2022, ONS, 9 March 2023, ons.gov.uk

[4] Nadia Khomani, English National Opera to receive £11.46m from Arts Council England, The Guardian, 17 January 2023, accessed 22 December 2023

[5] Train Driver Salaries in United Kingdom, Glassdoor, 20 December 2023, accessed 22 December 2023

https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Salaries/train-driver-salary-SRCH_KO0,12.htm

[6] David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: The Rise of Pointless Work and What We Can Do About It, Penguin, 2018

[7] https://www.a-n.co.uk/paying-artists/

[8] https://padwickjonesarts.co.uk/

[9] Doug Smith, $750 a month, no questions asked, improved the lives of homeless people, Los Angeles Times, December 19 2023, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2023-12-19/750-a-month-no-questions-asked-improved-the-lives-of-homeless-people

[10] Jon Henley, 'It’s a miracle': Helsinki's radical solution to homelessness, The Guardian, 3 June 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/jun/03/its-a-miracle-helsinkis-radical-solution-to-homelessness

Alistair Gentry March 2024

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.