The Zero-Hour Artist

Self portrait as the Earl of Rone, 2021 by Lucy Wright

My first zero-hour job in the arts was when I was eighteen, working at the city public art gallery. I was given as many shifts as I could handle, fitted in around my degree studies, and an hour off for lunch, when I’d slope around the charity shops and eat my sandwiches out of the plastic wrap.

As a working-class kid from an agricultural community in the North, I felt like I’d really lucked out, getting to spend my days in the cool, clean, palpably middle-class spaces of the gallery, watching quietly as the relatively few visitors we received made their way around the exhibits, like faithful adherents to a religion I’d heard of, but not yet been fully converted to. Sometimes the gallery was empty, in which case I’d be allowed to read my book, and occasionally we’d have a private view, where I’d be invited to take home the extra pastries and cakes that didn’t get eaten. I was paid £6.70 an hour, which was more than most of my friends earned working in shops and cafés—and I felt like a life in the arts was…kind of a doddle.

Twenty-ish years later and the tables have turned. I now earn significantly less working in the arts than many of my peers in other sectors. I earn a fair bit less than the national average, too, in spite of my PhD and raft of experience (although I am lucky enough to be paid more than both the National- and the Real Living Wage in my work for an arts charity, making me better off than the 3.5 million people across the UK, who still don’t). My working life is a patchwork of salaried employment and freelance work as an artist, although if I’m honest, it’s only the salaried part that breaks even. And while I’m pretty active in my practice as an artist—at least if my Instagram is to be believed—I generally find that I spend more money on making my work than I get from commissions, projects and sales. That feels like admitting failure to say, but I know that I’m not alone. According to last year’s report from Industria, only 3% of artists live comfortably from their practice, with a whopping 90%—including me—who work other jobs to stay afloat. Even when we’re fortunate enough to land a paid gig as an artist, the median rate for our labour scumbles along at £2.60 per-hour. Like many others, my modest part-time wage also has to subsidise my underpaid work in the arts. It sounds kind of ridiculous, but it’s a choice that I’ve willingly made.

Here’s where my privilege comes in. My partner works full-time in academia and when we bought our first home last year, we did so in a part of the country where house prices are ranked third lowest in the UK (it was still too frickin’ much though). I’m also white, able-bodied, and don’t have kids. My income, while needed, doesn’t currently have to deliver at its maximum potential—although this doesn’t stop me from lying awake at night sometimes, worrying about the future and all the possible, even probable, pitfalls of my under-earning. I come from a line of independent, bread-winning women, who taught me the importance of having my own money, being able to pay my own way. And I can, I do. Just. But prices are spiralling and I’m still afraid.

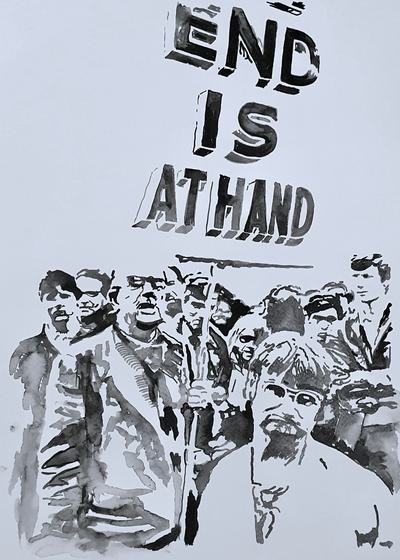

So why do I do it? If you’re an artist reading this, you’ll probably already know the answer. It’s because I love it. Perhaps irrationally so. I love my day-job supporting artists, where I hope that we provide a small sliver of care in a sector that’s often sorely lacking it. And I love art, both making and experiencing it. There’s nothing for me that beats the gleeful purpose of working with materials and ideas; of creating an intervention and watching it land, knowing that you made it happen (or helped it along)—or the vicarious pleasure of seeing others do the same. There is so much in our world to fear and despise, so much that keeps us apart from each other and it’s easy to feel forced into positions of helplessness. But art allows us to have a voice—however quietly heard—that reassures us that we exist, that we can do things, and we matter. And when a whole bunch of us do this, our combined efforts can sometimes create real changes in society. Not all art does this, by any means. But still…the potential feels almost sacred. Many of my favourite people are artists. Being an artist is my favourite thing to be.

Does this mean I don’t deserve to be paid? No, not inherently. Enjoying one’s work doesn’t automatically mean that it warrants less remuneration, however much capitalism might wish it were so. Some people really love spreadsheets. And selling advertising space. But at the same time, if the thing you do doesn’t really make any money, isn’t that sort of like…a hobby? Again, not necessarily. Some people’s hobbies make them plenty of money—hello, portfolio landlords!—and ‘hobby’ seems to imply a degree of amateurism, when some of the most skillful and experienced professionals I know are under- and un-paid for their work in the arts. No, it’s just a happy coincidence for the sector that a large proportion of its labour-force are committed to making their art regardless, just for the love for it. We’re a zero-hours creative workforce, primed and ready-to-go with up-to-date skills and a progressive agenda, developed on our own time and our own dollar, always on call for the next opportunity that may come our way. No sick pay or holidays required!

I’m not completely sure what I think about this. As a student, my zero-hour contract felt like an advantage. If I had time to spare, or extra bills to pay, I could take on more shifts; if I had assignments to submit, or exams to study for, I could step away for a while, knowing that the job would still be there when I returned. As an artist, it’s less beneficial. Because it’s not like I can just go away and do something else. Not really. The times when I’m not being paid to make art, I’m still making it. I have to. Partly because it’s a core part of who I am, but also because it’s crucial for keeping my practice in good shape—by which I mean hopefully thoughtful, fluent and responsive to the times we’re living in. It also needs to be fundamentally visible in a crowded marketplace. (Without all that unpaid labour, I’d be unlikely to get another gig at all). And equally, when I need a bit more cash, it’s not as if I can just take on some more art-making, to plug the gap. Quite the opposite, actually. I’m speaking primarily from the standpoint of contemporary visual art here, but it probably applies to other parts of the sector too.

But at the same time, most people—except for the very, very privileged—have to work for a living, generally in jobs that are bearable at best and often soul-sapping as standard. And we’d probably all like to be paid for doing the things we love, like say, attempting to pet each of the neighbourhood cats in turn or watching aircraft disaster shows on Netflix, but it’s hardly likely unless we’re able to find some way to tap into an income stream that transforms the activity from *doing the thing* into *making content about doing the thing* (which probably drains the joy out of it anyway). I’ve written elsewhere about arts sector exceptionalism, and I know full well that this is what it sounds like when I complain to my friends back home about not making enough money as an artist. One friend—who works in social care—teasingly describes my job as ‘gluing leaves to things’ and another—an NHS administrator—recently exclaimed, ‘but your work’s like being on holiday all the time!’ when I mentioned that I’d not managed to take a break this year. Both comments came from a place of love, but it’s sort of good to know that this is how we are seen in the wider world.

Except, I don’t completely agree with this either, and probably for a slightly controversial reason. Because I actually think the arts ARE exceptional. Yep. This isn’t just an ethics of convenience (I hope!). I don’t necessarily believe that artists are exceptional people, at least in terms of who they are, or might be. And I know that there are LOTS of exceptional roles in society that probably make an equal and greater contribution while also being grossly underpaid. But I DO believe that making art is a core societal good, comparable to how playing sport is generally perceived, for example, or education. We rarely question the importance or validity of these things, even when they don’t directly make money, and for good reason: they’re accepted parts of our collective value system. But it wasn’t always this way. Just over one hundred years ago, the Fisher Act enforced compulsory education for all children aged five to fourteen, as a result of widespread advocacy, including from the trades unions, who aligned access to education with democratic citizenship. Prior to this, the arguments for extending educational opportunity had focused on enhancing national efficiency and productivity. But in 1918, learning was reframed as a ‘right’ for all, something that held intrinsic—not just financial—value.

That’s what art should be. An intrinsic citizenly right. And not in the ‘deficit’ sense of jollying the povos into dipping a toe into institutionalised art forms spearheaded by far more advantaged folks. The arts needs be open to all people—as creators and professionals as well as audiences, but right now, the only ones who are really able to pursue a career—in the contemporary arts at least—must have some other kind of financial backing, whether self-generated or inherited/spousal. This makes it fundamentally inaccessible, however many socially engaged projects promise to ‘transform’ underprivileged communities. And this isn’t just an issue because it’s unfair—although it is—but it also positions art as a luxury, something nice that you can do if you happen to have had the good sense to be born wealthy.

Perhaps that’s why I always feel a bit uncomfortable when I hear people trying to make the economic case for the arts. I get it. This is the world we live in…a world in which we appear to know the cost of everything, but rarely its value. But if you can’t beat ’em, do you really have to join them? We need to advocate for the arts, not because they are good for the economy but because they’re good for people, good for us—or at least they could be, if they were properly funded. I think we need to conscientiously object to the efforts to force us into boxes that don’t fit, that were never meant to fit us. We need to accept that a whole swathe of contemporary art making doesn’t make money, just as educating four-year-olds doesn’t directly raise cash, and your local 5-aside team that plays on the rec ground probably isn’t raking in the big bucks. So what? Our value functions on a different plane.

And our zero-hours workforce? Give us some version of the Intermittence de Spectacle like they have in France, or better yet, universal basic income for all. I dunno, I don’t have the answers. The whole system needs shaking up. But as both the architects AND the engine room of a fundamental societal right, artists deserve better than a life of exploitation on the breadline.

Artists

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.