'Welcome to the club?' On disability, poverty and exclusion in the arts

Commissioned as part of the 'Artist Exploitation' series, in January 2024

Several years ago, a once-famous musician friend, on hearing I’d just completed 6 months’ work as part of an ‘art collective’ which promised a flat fee and then took select members of the collective (three of their ‘friends’) B on a European tour with our work, slapped me on the back and said, ‘Tina, you’re just not part of The Club. You’re a triple threat; you didn’t go to art college, you’re a disabled woman, and you’re working class’.

I later found out that out of the four disabled artists who took part (were we just a box that got ticked for funding?), none of us were paid, and contact with the other, able-bodied artists and organisers didn’t just fizzle out; it stopped dead. After a little digging we found that the organisers had three grants totalling around £60,000 (plus, a lovely summer travelling around Italy and France with our work).

I’m working class. My dad was a miner, and girls like me didn’t go to college, our aspirations amounted to factory work and marriage. University was an impossibility and an interest in art was met with suspicion and a ‘who do you think YOU are’? attitude (which continues even now. Art isn’t for the likes of us; it's only for posh people).

After a life-changing illness, my ‘hidden’ passion (because art was never a hobby; it was always everything to me) became my life. I entered local opens and won, I entered national opens and made long lists, then short lists and then…I won! But I had no idea how the art world worked.

How could I get my foot (or wheelchair wheel) through the door of the ‘Art World’? I thought it might be as simple as approaching my local (or any) gallery, showing them my work and smiling hopefully, and then the magical door would open for me… Phoebe Saatchi would stand, arms open with a welcoming smile, and Tracy Emin would whisper ‘welcome Tina, you are an artist… ‘, hand me a tiara and hang my painting on the wall.

WRONG.

Over the last few years I’ve joined art groups, gone to countless Zoom meetings from all sorts of arts organisations, attempted to ‘network’, entered opens, applied for funding and jobs (and failed), worked for no pay, worked for less than minimum wage, asked for help, applied for help, contacted numerous people, galleries, artists and organisations for advice and I’ve come to the conclusion that my friend is right. I’m simply not part of ‘The Club’.

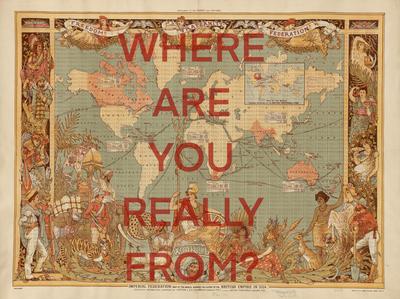

What is ‘The Club’ I assume you’re asking? Well dear reader, if you are asking that, then I fear you may be a part of that club, and therefore unknowing or perhaps unwilling to admit that you are a certain class, colour, gender and/or able-bodiedness. Perhaps you have a comfortable background or have even been lucky enough (despite your class, ableness, gender or colour) to break into The Club, and now protect your place at the head table with vigour and a solid unbending belief that meritocracy exists.

Here’s a word I’ll be using a lot – meritocracy. Let me explain. In the case of an art career, meritocracy means that an artist is ‘successful’ solely on their talent and ability, and not by their class, body, colour, status, education or wealth. But this isn’t true, not for me, and not for the majority of the disabled, working-class artists I know. Quite a sweeping statement, but I will attempt to provide you with proof.

Despite trying for years to find and build relationships with other artists, and failing (I never tell anyone I’m disabled unless I have to – Artist FIRST, disabled second), I found help and a sense of ‘belonging’ from Disability Arts Cymru. For the first time I could talk to artists who have similar lived experience and were open and communicative to me. These are some of the people I turned to for opinions on if meritocracy is simply a fallacy. For balance, I chatted to 2 other artists (no one else would engage), both known in the arts world and both from privileged backgrounds. One admitted the ‘leg up’ of their privilege, is aware of it and protests against the unfairness of the system to the point of founding an organisation open to all artists, with particular emphasis on working class arts. The other absolutely believes they are working class (their grandparents were landed gentry, both parents highly paid professionals in the arts) and meritocracy got them where they are now. When I asked why they thought of themselves as working class (speaking to me from their flat/studio in London bought for them by their parents), they replied… ‘Well, because I work…’.

I’ll also include information from three studies that look at social mobility in the arts. These are Social Mobility and openness in creative occupations since the 1970s; Panic! Social class, taste and inequalities in the creative industries, and #weshallnotberemoved UK Disability Arts Alliance 2021 Survey Report: The Impact of the Pandemic on Disabled People and organisations in Arts & Culture).

One of the core subjects of each is class, and how in layman’s terms, if you’re working class and want to be successful in the arts world … you’re stuffed.

Are the working classes in the UK the free labour of the Arts world and a ‘stepping stone’ for other more affluent artists? And is a successful career in the Arts more to do with your class/background (privilege and confidence wins over talent)?

Let’s look at the scholarly information. Brook, Miles and Taylor suggest that creative occupations are not, and have never been ‘open’ to everyone, arguing that ‘creative jobs have remained unequal in regards to the class of that person since the 1970s’. [1]

Back in 2017 after a Labour party survey stated that the class-divide in the performing arts was putting working class creatives at a disadvantage, working-class actor Christopher Eccleston told Sky news that his working-class roots put him at a disadvantage because he wasn’t a part of the ‘boys club’ of public school-educated actors. This caused much chagrin from his contemporaries.

‘If ever I go up against anybody who is from a middle-class background, or has been public school educated … I’m at a disadvantage… it’s a “boys club”.… I could not have gone to drama school today – my parents could not have afforded (It). People like me are not gonna come through anymore. If you are working class …you are at a severe disadvantage’ [2]

Similarly, working class actor Michael Sheen was so frustrated at the lack of opportunities for working class creatives he formed A Writing Chance. [3]

‘We have to make sure that talent is nurtured… fundamentally it’s about diversity… and fairness, it’s just not fair that certain people because of the accident of birth and family and geography get certain opportunities and others don’t.’ [4]

Brooks, Miles, and Taylor go on to make several more points. Between the 1980s and early 2000s, children from more affluent families earned more in the arts than those from working-class backgrounds, and long-term employment is mostly achieved by those from ‘advantaged backgrounds’ with a marked ‘fall in recruitment from working class backgrounds’.

Education makes little difference to a successful career in the arts either. With or without a degree, an artist ‘whose parents are more privileged have double the odds of gaining creative work compared with those from working class backgrounds’. [5]

Living in London, being white, male and able to work for free is a huge bonus, and the ‘likelihood of a person accessing core creative work is strongly associated with their class origins. The class advantage is in addition to the advantages this group already holds, there is no evidence this is a new phenomenon’. [6]

Brook, O’Brien, Taylor went on to author a similar paper looking at class in the Arts with Panic! Its Arts emergency! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries. Out of 2,487 participants when asked what was the biggest influence on a successful arts career, meritocracy won, the caveat being that by the authors admission the vast majority of respondents worked in the arts world, and were ‘highly-paid white men’. These participants wrote they had ‘a small network of friends, and in the main, they did not know anyone who worked in a (typically working-class) manual job’.

These are the people who are the heads of arts organisations, the managers, curators, artists, gallery managers, influencers, the people in control, the dictators of our fate. [7]

The #Weshallnotberemoved paper on the impact of the pandemic on disabled artists in 2021 was a small survey of only 131 respondents, but nevertheless has some interesting points on class (not all disabled artists are working class!). 67% went to a state school and thought of themselves as working class, 8% went to a private school, the author noted:

‘Significant numbers knowingly or unconsciously downgrade themselves to ‘less than middle-class’ than their backgrounds actually are. Comparing themselves to people much richer – instead of those who are poorer’. [8]

Much like one of the artists I spoke to about class, it appears they either ‘think’ they are working class (perhaps because they don’t know what it means?), are unknowing, or are unwilling to place themselves in that group.

WHY does class and privilege matter, and what have they got to do with exploitation in art?

Brook, O’Brien and Taylor’s research underlines that all art forms are populated and run by the more privileged in society.

In 1981 around 25% of people working in the arts were working class, by 2012, only 12% were working class, and that percentage has continued to decrease. [9]

If you are a real working class artist without an arts degree, you will find it nearly impossible to join ‘The Art Club’, and the belief that talent will always shine through, and the best jobs will be bestowed upon the most accomplished, is a lie.

There is no such thing as meritocracy in art: it’s an us and them situation.

They have a network formed by who they went to college with, perhaps their families/friends are already part of The Club giving them admittance, maybe they have a monied background and don’t need to pay rent, and as S. Koppman suggests, money is integral and perhaps one of the biggest barriers for lower class/disabled/ethnic artists, where the lack of economic support is ruinous.

The finance - or rather a safety net of money needed to start and maintain a career in the arts ‘can only be achieved by those with money, contacts and privilege’. [10]

On a personal note, this may sound like I have a chip on my shoulder, am jealous, misinformed, or plain wrong, however, published research (and personal experience) suggests that to be successful in the arts, apart from your network and class, you must be able to access money to live without relying on state benefits, and simply proclaiming you ‘lived in a squat’ does not mean you couldn’t afford to pay bills and eat.

All the studies noted that unpaid work in the arts is endemic, and this is where the divide between classes is most prominent. Almost all artists see unpaid work as inescapable no matter what their class, however people from affluent backgrounds mainly believe working for free is ‘a choice’, and although not ideal ‘leads to a career with pay’. [11] This career may be enabled by them being part of a network of equals, and not having to worry about finance to live.

There is no relevant research on disabled people in the arts, and the aforementioned papers don’t comment on the working class/disabled experience in regards to subsisting on state benefits. It would be presumptive to say that all disabled artists are working class, it’s simply not true as I know several who come from affluent backgrounds and therefore have less financial stress than most. However, from personal and the lived experience of some contemporary artists, we live precariously, with no financial safety net. The majority of us rely on benefits to survive as we cannot find any full-time work because of our disabilities.

Not coming from an affluent background and being reliant on the benefit system to live is a major, and unseen problem when you are an artist.

The benefits system itself is black and white with no grey areas, you either work, or you are ‘too ill/disabled’ to work, and the process of obtaining these benefits, particularly PIP (Personal Independence Payment) is nothing short of torture. [12]

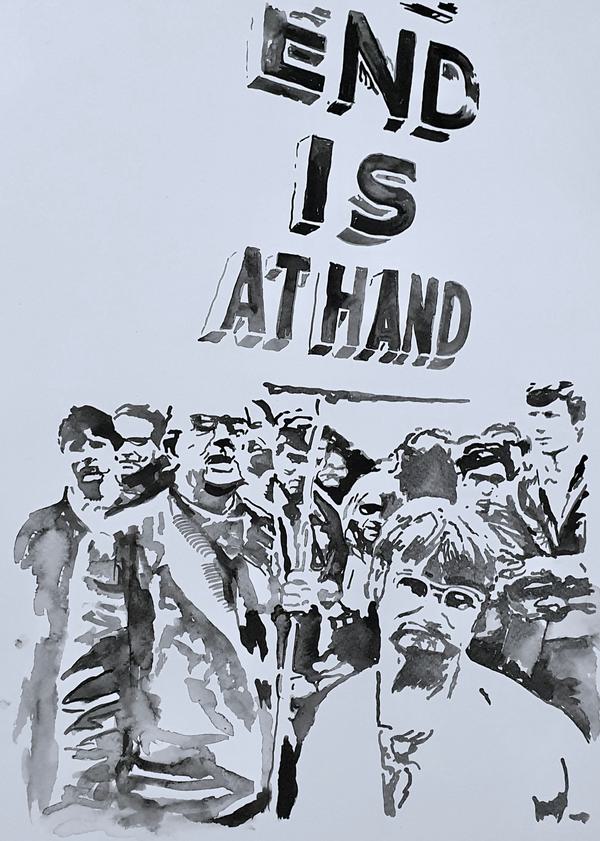

If you have no financial security, no ‘safety-net’, working for free is impossible, yet, we have all done it because it is the only way available for the poorer working class and disabled artists to be ‘seen’.

We also find it’s practically impossible to become part of a network that includes the elite in art, the people we NEED to know to be successful, the gallery heads, the curators, and other artists. Most of us were unable to go into further education, few of us have engaged with a gallery and even fewer have been a part of or had and exhibition.

Why?

In my (and others) experience, the curators, galleries etc simply don’t know who we are - or what we do. I believe the reason for this is simple: they simply don’t look. They remain in the confines of their safe networks.

In a Zoom meeting I asked a prominent arts person how we can be seen, they told me that they are ‘always going to people’s studios to look at work’, I replied I hadn’t got a studio and worked in a bedroom, after some stuttering, they didn’t come up with a cohesive reply. No studio, too far away from the city, and no mention of talent. We are unseen, unheard, invisible, poor and ready to give up, because we are not in a network and are not part of ’The Club’.

Before writing this piece, I asked other DAC members for their experience in working for free. I had several replies and all the respondent’s told stories of working on projects for no pay, with the explanation that the people in charge told them it was ‘good experience’. I asked ‘where did that ‘good experience’ lead? All responders replied ‘Nothing/nowhere’. The ethos of free labour for the working class and disabled artist is ‘experience’ (and being told you should feel ‘lucky)’.

After being a part of a project for a large arts organisation where I suggested that the money left over could perhaps be distributed amongst those of us who had worked for free, was met with incredulity, I was told in no uncertain terms that I should be ‘thankful for this opportunity’, and that I ‘Was lucky to experience what it was like to be…a real artist’ (this came from a white, middle-aged male, arts educated, possibly affluent, head of an arts organisation).

Another artist shared with me a similar story, who on being told she would be paid for work which was used as part of an exhibition about disability, has remained unpaid and has been completely ignored by that organiser.

They told me, ‘their privilege makes them entitled to expect everything for nothing’.

The pandemic opened my eyes to the way the art world works, in one way it was fantastic, everything seemed to open up via Zoom, but at the same time, going to countless arts meetings and listening to endless platitudes on how ‘they’ were open to all artists, including the disabled, made me realise just how dire the situation is, because the truth is – they are open, but only to people in their networks. Again, ‘we’ remain unseen.

One meeting involved galleries and artists. The speakers all held powerful jobs and appeared to be part of the same network, they were discussing their careers and how they got into the Arts.

Tales of art college (all went), then work in galleries in worldwide, living in Paris for the ‘vibe’, curating in New York then…the V and A! The Royal Academy!

I sat knowing that later that day, I would be visiting a foodbank, and couldn’t afford to put the heating on.

They belong to another world, part of the Club I don’t think I’ll ever be accepted into or a part of because no matter how talented I am, I’m either invisible, or remain a ‘free creator’, a stepping stone for the ‘others’ who simply can’t or refuse to see our cavernous differences.

Is there an answer? How can we be seen, valued, and PAID by this group of influential people, and will the The Club open it’s doors to us? I could end this with a list of suggestions, ways to include ‘us’, but despite being eternally hopeful, from experience, there is no glimmer of hope on the horizon. Research shows that essentially nothing has changed in the arts world. It is full of the affluent (whether or not they realise it), the educated, the entitled, and the confident.

The art world belongs to them. They know each other, they know how to fill in funding forms, they use ‘Art Speak -word salad’ that we don’t understand, and working for free is a pain but they can still pay the rent. Perhaps they see some of us through sheer luck, otherwise we remain unseen, unknown, unimportant.

Until the people with power in all the arts raze The Club to the ground and have a word with themselves about spreading their nets wider than their trusted network, providing opportunities by ACTIVELY seeking us out, giving platforms and inclusion for all artists—meritocratically—nothing will change, and the huge talent out there in foodbank land, will remain unknown.

Endnotes

- Orian Brook, Andrew Miles, Mark Taylor, British Sociological Association Journal, Volume 57, Issue 4 ‘Social Mobility and ‘Openness’ in Creative Occupations since the 1970

- Tom Connick NME August 2017 Christopher Eccleston hits out at lack of working class representation in the arts - NME

- A Writing Chance - New Writing North

- Channel 4 news Michael Sheen backs working class writers in creative industries - YouTube

- Orian Brook, Andrew Miles, Mark Taylor, British Sociological Association Journal, Volume 57, Issue 4 ‘Social Mobility and ‘Openness’ in Creative Occupations since the 1970

- Boliver V (2017) How meritocratic is admission to highly selective UK universities? In: Waller R, Ingram N, Ward MRM (eds) Higher Education and Social Inequalities. University Admissions, Experiences, and Outcomes. London: Routledge, pp.37–53.

- Orian Brook, David O’Brien, and Mark Taylor. Create London. Panic! Its Arts emergency! Panic, social class, taste and inequalities in the creative industries

- UK Disability Arts Alliance 2021 Survey Report:

The Impact of the Pandemic on Disabled People and organisations in Arts & Culture

Compiled by Alistair Gentry. Edited by Andrew Miller - Brook, Miles, Taylor, ‘Social Mobility and ‘Openness’ in Creative Occupations since the 1970s

- Koppman S (2016) Different like me: Why cultural omnivores get creative jobs. Administrative Science Quarterly 61: 291–331

- Brook, O’Brien, Taylor. Create London (2018). Panic! Its Arts emergency!

- Personal Independence Payment (PIP): What PIP is for - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- Lastly, a link to an article from July 2023 in the Evening Standard by Joe Bromley as something for you to contemplate, and underlining if you will, the Club.

Meet the YLAs — the new young London artists | Evening Standard

‘Meet the YLAs — The New Young London Artists’. ‘Disruptor’ 1 - Isaac Benigson: artist and socialite’.