On Mining

by Adam York Gregory

Commissioned by Axis as part of the 'Artist Exploitation' series in January 2024

[LAND OF IRON]

Nick slides the heavy wooden cover back to reveal a thin wire safety mesh and a dark square, about half a metre on each side.

The dark square, Nick tells me, is the ventilation shaft.

I lean over and a warmish air that smells sweet and acrid at the same time brushes against my face.

I stare into the hole and I can see, at best, a few feet of the sides before the deepest darkness takes over. Despite that, I can feel the unfathomable depth.

Men worked down there in the dark, claustrophobic embrace of the earth. They were mining iron ore. Exploiting this natural resource that had previously been collected as Ironstone on the local beach.

These men made their living seeking the valuable resource, the material that would later turn places such as nearby Middlesbrough into industrial behemoths.

And just as they exploited the very ground upon which they walked, so too were they exploited by the owners of the mines.

They were paid little, the work was hard. Their communities were forged from fishing villages and turned into workers rows.

You can, of course, make the case that this brought modernity, and perhaps even purpose to their lives. It gave them a stake in the economic system.

You could also argue that they were merely a means to an ends.

As I'm stood there, bending over a ventilation shaft at the Land of iron in Skinningrove, I feel a sense of vertigo.

Or maybe embarrassment.

Because I'm there to exploit people too…not as an a miner, but as an artist.

---

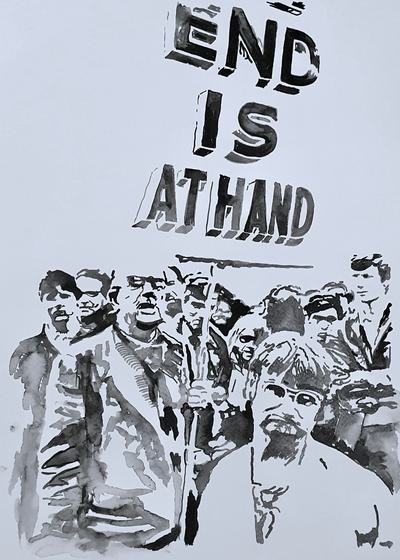

[BIG SOCIETY]

On the 19th of July 2010, the newly elected Prime Minister, David Cameron, made a speech in front of an audience in Liverpool.

It is now known as ‘The Big Society’ speech.[1]

On the face of it, it is a rather optimistic call to arms, asking the British people to band together, to work as communities, in communities. To pick up the slack, to engage.

Cameron talks about the things we do that are our duty and the things that we do because they are our passion.

Big society is about empowerment. It is about freedom.

It features the word community seventeen times

‘If it unleashes community engagement - we should do it.’

It all sounds rather wonderful.

Except...

The speech was delivered in 2010. It followed one of the most devastating economic collapses of the last one hundred years, the 2008 banking crash.

This crash was caused by the sub-prime market, where rather wealthy traders traded in debt. They got so confused in their money making frenzy that they forgot to keep track of what was good debt and what was bad debt.

Good debt is the sort that gets paid back, with interest, bad debt is the sort that ends up in people going bankrupt owing money and defaulting on mortgages. The markets lost confidence and prices tumbled.

There were runs on banks. Queues outside Northern Rock where people were trying to get their money before the bank itself became insolvent and collapsed.

Millions of people were made significantly worse off.

Fortunately, those responsible for the crash were bailed out by one of the single biggest transfers of public money, from the poor to the wealthy.

Thankfully, the bankers were saved.

This, however, left a problem. There was no money left for public services. Libraries, schools, hospitals, public arts all were left in deficit.

The incoming Tory government had a plan. They called this plan, 'Austerity'.

Everything would be cut back. We would make do with less. We would tighten our belts and cut the cloth appropriately. It would be hard, but it would get the economy back on track.

Sure, it would mean millions of working-class people suffering, unlike their ‘banking-class’ counterparts, but that was a sacrifice the Tories were willing to make on your behalf.

Austerity was touted as a short period of re-alignment.

As we approach our 14th year of Austerity, schools are literally crumbling. Waiting lists at hospitals are at a near all time high. Public money for the arts is scarce. In essence, we have spent fourteen years of suffering for very little gain.

Still, the bankers are now enjoying a time of the greatest disparity between the poor and the wealthy.

Alongside this transfer of money came a parallel transfer. A transfer of responsibility.

Big Society was the branding campaign to launch this.

The government was no longer responsible for your crumbling services or your pillaged communities, you were.

You were going to pick up where they fell short. You would provide the foodbanks that replaced their welfare schemes. You would look after the children as the Sure Start centres closed.

Austerity meant demanding charity.

As an artist, you were no longer responsible just for creating art, you were conscripted into the realm of social work, where the metric of your success would be measured, not in terms of artistic excellence and expression, but in terms of 'engagement' and 'community'.

---

[COMMUNITY]

What exactly is a community?

Is a community geographically bound?

Is a community temporally bound?

If a community is split in half does it become two separate communities?

Can one person be a community?

Can one person be part of more than one community?

Does the produce of a community belong to the individuals, the community, or the people that make money off that produce?

Can people in a community disagree with each other?

Can any one person represent a community?

Can anyone outside of that community talk on behalf of the entire community?

If something so complex, fluid, and nuanced as community is used as a metric, is it possible that we can bend that term to mean anything we want it to?

---

[SLAG]

Originally folk collected ironstone, a sedimentary rock that contains a significant content of iron ore, from the beach at Skinningrove. Often it was the wives and children of the fishermen that worked out of the bay.

In September 1847 Frederick Okey came to Saltburn to pay the folk who gathered nodules of ironstone from the beaches. Whilst there he met Anthony Lex Maynard, who walked him to his property and introduced him to a large chunk of ironstone that jutted out from the ground.

On August 7th, 1848, the first mine in Cleveland opened in Skinningrove. It was the first of 83 ironstone mines in the region.

The landscape would be forever changed, as would the communities that lived upon it, and slowly began to work below it.

One change to the landscape would be the cliffs over Cattersty beach. If you walk along there now you could be forgiven for thinking that they are the result of some sort of pyroclastic lava flow. In a way they are, except they are very much man-made.

The process of mining results in iron ore being smelted into iron and slag. The slag is the by-product. The waste.

In this case the nearby foundry just dumped it over the cliff.

---

[ARTIST IN RESIDENCE]

Aired on 22 July, 2018 on Channel 4, Artist in Residence: Sex Clinic featured performance artist Bryony Kimmings spending time at the Whittall Street sexual health clinic.

Sam Wollaston in the Guardian review of the show wrote:

"Bryony is more interested in the 2,000 or so people a week who come in to get help, especially the ones who are prepared to spill the beans about the most intimate parts of their lives. She likes real lives, real stories, real people, and she wants to make art with, about and for them."[2]

In many ways it was a televised re-tread of Bryony's own 2010 show 'Sex Idiot', that used her own experiences to create material. In the 2018 version, Bryony chatted to a range of people using the service. It turns out that sexual health is somewhat of a pretext for talking about other issues.

Wollaston describes it using the following phrase:

"Bryony spends time with them, mines their lives, consensually and collaboratively."

Mining. It's a word Kimmings also uses in the show to describe her process.

Can mining be consensual when it involves humans?

It depends upon who benefits, perhaps.

Does the resource mind being mined? Do they get as much out of it as the miner?

Kimmings continues to make topical work, often with communities. On her website the shows are neatly described as "the one with all the booze", "the one with the nine year old" and "the one with songs about the c-word".

Are you more than just the resource you are being mined for?

And what remains once you have been mined? Once the stage gold has been extracted?

A slag heap of messy, complex human life.

---

[SLAG]

We are now waking back through Middlesbrough. A town that earned the nickname 'Ironopolis' on account of its booming trade during the industrial revolution.

We are being given an ad-hoc tour by Bobbie Bailey, a researcher in urbanism and a co-director at Freestyle Community Projects where he helps appropriate unused and derelict spaces and turns them into functional community-driven projects.

He's also a massive advocate for Middlesbrough. His love for the place is rather infectious.

He takes us on a detour. He's excited by the road.

We look down at a patch, the tarmac has been peeled back. It's hard to tell whether it is deliberate or whether it is caused by the same affliction that has riddled most of the UK's roads with potholes and crevices.

Local council austerity, isn't it? Make do with less road surface.

Looking down we are greeted with a silvery sheen. Rows of regular square shapes like geometric basalt.

"They're made from the slag of the ironworks", he says, "They're called Scoria bricks".

They are beautiful.

---

[EXPLOITATION]

I'd like to share a little about some specific exploitation I have dabbled with, time to time.

I'm not proud of this, and the fact that I realise my complicity in it doesn't absolve me. I know that.

I don't make enough money to survive, financially, as an artist. I have to top it up with some side hustles. Everything from the occasional data entry through to corporate design work. I'm not too proud.

However, one of the most lucrative gigs and one that strokes my ego, is to attend a university to give a talk to aspiring artists about having a career in the arts.

I'm supposed to stand there and tell them it is a viable career. That the thousands of pounds they are paying in tuition will help them lead a satisfying working life.

I do this knowing that it is a lie. I do it because I'm being paid well to say so. It's in the universities best interest that I hold the line, and they make it in my best interest to do so.

Occasionally, I get a pang of guilt and tell students the truth. I tell them that the arts are a great career if you enjoy trading creative freedom for financial uncertainty. It nourishes the soul, but seldom the bank account. With the exception of a lucky few, money is sporadic and often far less than your labour deserves. You spend just as much time chasing money as you do making art, and ultimately the art you can afford to make is tempered because either you have to pay for it with your own reserves, or you alter it to fit the criteria of funding bodies.

I'm exaggerating, of course, but part of being a good artist is about maintaining integrity whilst working in a society. I think there's truth in it.

Often, I am ashamed to say, I talk about all the brilliant things I get to do, and gloss over the unseemly side. I convince myself of that the reason I am there is not to prepare them but to excite them. Keep them going on that final push through education.

I am there to tell them, that if they are lucky, one day they might find themselves stood where I am delivering the same message.

And when I do that, I'm involved in a pyramid scheme.

---

[LANGUAGE]

The language of austerity, and of Big Society is fascinating.

The New Economics Foundation released a paper in 2018 called 'Framing The Economy'.[3]

It starts with the line, "What is the story of the economy in Britain?". It's about who controls the narrative.

And that narrative, predominantly was, and continues to be, that social justice is a luxury.

You can't have your pudding until you've had your dinner... You can't have public art until we save the libraries... You can't have libraries until you've finished fixing the NHS... You can't have a functioning NHS until the national debt is reduced.

The paper is fantastic at explaining how we can resist this. It also sections the issue under headings such as 'Story', 'Audience' and 'Vision'. Three words that should be familiar to any artist.

It illustrates several of the ways in which the narrative is manipulated.

‘People are inherently greedy’.

‘Regulation is bad’.

‘Outsiders cause problems’.

‘Hard work leads to success and failure is due to a lack of hard work’.

What ‘Framing The Economy’ illustrates is that the ideology of austerity, and the exploitation it encourages, is delivered primarily through language.

It is the language of neoliberalism, of finance and banking cloaked in the language of socialism and care.

Furthermore, it adopts a position that ordinary people aren't capable of really understanding how it all works. It posits that the public need very specific experts to talk about the narrative of their lives in terms that make it make sense. Almost always, those experts are not from those communities, but instead are the ones that benefit from their suffering.

It's a little like mine owners talking on behalf of the miners.

---

[HUG A HOODIE]

In 2006 a think tank based at Kings College London called The Crime and Society Foundation released research that suggested that increasing Tory hard-line crackdowns on crime were failing because they failed to address the underlying causes.[4]

Those underlying causes were of course intrinsically linked to Austerity. They were the widening disparity between the rich and the poor. They were the failing social services and crumbling public institutions. They were struggling schools, operating on ever shrinking budgets and the good will of teachers being pushed to breakdown.

There was an increased focus on 'antisocial behaviour'. Not the type of antisocial behaviour where someone greedily takes millions of pounds in bonuses whilst their business tanks leaving people robbed of their life savings, but the sort of antisocial behaviour where kids hang around on the streets because all of the youth centres have been closed down.

Rather than attempt to deal with these underlying causes, David Cameron proposed another approach hinting at what would become The Big Society.

In a speech delivered in 2006 to a conference organised by the Tories' social justice task force, Cameron said:

‘The hoodie is a response to a problem, not a problem in itself. We—the people in suits—often see hoodies as aggressive, the uniform of a rebel army of young gangsters.

But hoodies are more defensive than offensive. They're a way to stay invisible in the street. In a dangerous environment the best thing to do is keep your head down, blend in. For some the hoodie represents all that's wrong about youth culture in Britain today. For me, adult society's response to the hoodie shows how far we are from finding the long-term answers to put things right.’ [5]

He never said the phrase, 'Hug a Hoodie'.

The first use of 'hug a hoodie' is attributed to Vernon Coaker, Labour MP for Gedling.

In an awkward pivot from their own 'Respect' agenda, Labour chose to mock the position as being soft on crime.

In hindsight, neither side got this right. Fundamentally they created a division between people in suits and children in hoodies. Neither saw this as a holistic society, and both failed to appreciate that the failure of the state was the true cause of the apparent unrest.

The Conservatives tried, once more, to make their job the responsibility of the British public, and Labour responded by provoking them into steering harder into a 'tough love' approach that criminalised the youth.

Both sides attempted to exploit the fears of an already-strained public that had enjoyed six years of brutal funding cuts using language of community, engagement and representation.

---

[SOCIAL WORK]

Sure Start Centres were initially introduced during the early 2000s to help reduce child poverty. They acted as targeted community centres, providing everything from practical support through to advice and guidance.

By 2010 there were 3,620 centres and several studies reported positive outcomes from childhood obesity, school attainment, parental job prospects and first-time offender rates.

The Institute of Fiscal Studies claims that at their peak, Sure Start centres prevented 13,000 hospitalisations a year among 11 to 15 year-olds.[6]

Between 2010 and 2020, 1,300 of those centres would be closed.

Meanwhile social work in the community had suffered a comparable fate. According to Social Work England(7) 20% of council services positions are vacant as of September 2022 (up from 16.7% in 2021), and there has been a 40% rise in the number of social workers quitting their posts in children's services.

According to Sarah Blackmore at Social Work England, this is because of a rising demand ‘high caseloads, inflexible working practices, disproportionality for our global majority colleagues, perceived low status and credibility of the profession… and of course the impact of funding issues’.

---

[SKINNINGROVE]

The mine was officially closed in 1958.

The blast furnaces at the local steel works were closed in 1971 and the workforce was cut to around 400.

Meanwhile the fishing persisted.

The Manx photographer Chris Killip arrived in Skinningrove in 1981 and worked there until 1984.

‘Like a lot of tight-knit fishing communities, Skinningrove could be hostile to strangers, especially ones with a camera... Skinningrove fishermen believed that the sea in front of them was their private territory, theirs’.[8]

In 1988 Killip won the Henri Cartier-Bresson award for his book, In Flagrante, which recorded the the lives of the communities living in the post-industrial landscape of the North East. There were only two photographs from Skinningrove.

Killip explained in a 2013 documentary(9) the reasons for this. He talks about his responsibility and the emotional complexity of working in that community. He talks of the tragedy of the day a boat over-turned and killed two young men.

Chris Killip died of cancer in 2020.

As he reached the end of his life, he felt able to publish the pictures that he had taken during his time there.

However, before he did so he posted editions of those photographs through every letterbox in Skinningrove.

---

[SOCIAL WORK]

To be a social worker in the UK you have to be registered with Social Work England, and that in turn requires that you have a compatible degree or post-graduate qualification. Typically it takes between three and four years of full time study to achieve this.

The courses teach things like accountability, how to deal with trauma, the law and legal contexts of social work. Ethics and politics. Working with the vulnerable in communities.

In some cases, more than we should be comfortable with, artists are talking and working in those same terms, filling in for cracks in our social system, and they are doing it completely untrained.

Untrained to deal with trauma in vulnerable communities.

There's a predominant wisdom that 'giving a voice' to people, and helping them 'share their stories' can do nothing but good, but mining can be dangerous. The roof can collapse in if you don't know what you are doing.

---

[BAD LANGUAGE]

You are filling in an application form.

You read the questions and observe the language being used. It isn't your language, but it is familiar. It's the language of Big Society.

There are questions asking you to justify your work in terms of 'community' and 'engagement' but little mention of 'vision', 'tradition', or 'aesthetic'.

You feel a pressure to convert your aims into this language.

And you know that you can't replace social workers, and that the stories of some communities belong to them, and them alone.

If you really wanted to help them you'd retrain.

But you don't want to do that. You want to be an artist.

You are an artist.

You see other artists cramming work into community contexts. It doesn't fit the work and it doesn't help the community.

But you want to be an artist, and you need the money.

And when you report back you report back in that same language. You talk about how many people were engaged. How many communities you involved.

You avoid the tricky questions about engagement and community. The questions that have answers that aren't just numbers in a little box.

This is the exploitation.

You apply in the language of Big Society, you report back in the language of Austerity and all the while you know that you have your full-time job, that of being an artist, and meanwhile you are expected to pose as a social worker, on already-stretched budgets with increased overheads.

Do more with less.

Like the teachers and social workers, this engine runs because you treat yourself as a resource to be mined and burned though.

---

[TRANSMUTATION]

A fishing village into a mining community.

A lump of stone into iron.

Iron into steel.

Galleries into after school clubs.

Libraries into heat banks.

Theatres into community spaces.

Artists into Social workers.

It's great that they arts are able to step up during this time. It's a testament to all the people that work in the arts in the UK that we are so ready to step up. That we want to make things better. That we are so ready to share what we have.

It all happens without extra financial support.

However, it is not a sustainable way to function.

There is a cost.

The cost is art.

I'm not just talking about the fact that if funds are spent on making sure the building is warm so that people can come and sit in it then there will be, logically, less money to commission new art. I'm also talking about the exhaustion and burnout that happens to all of the artists and staff that operate in these buildings as they too deal with the cost-of-living crisis, increasing rents and energy bills and pay that has remained mostly stagnant in the last decade.

Meanwhile, the money being spent on keeping these spaces warm and open is leading to record profits in the hands of energy companies that exploit the situation.

I'd argue that these people do this not because they find themselves talking in the language of Big Society, nor because they even needed to be told, but because they are good, kind people.

They do this, not for a community, but because they are the community.

They don't have a choice, and that's what is defining the exploitation, being forced to do something that ultimately is not in your own best interest.

And all this does is cover over the cracks and obfuscate the fact that Big Society failed.

---

[EXPLOITATION]

Exploitation is rarely a binary situation. Exploitation is a chain that the poorest and most vulnerable find themselves at one end of.

I'll be blunt with the metaphor.

Artists are the fishermen that ended up in the mine.

We are exploited as we step up as social workers in a black hole of ideological austerity, but we also exploit the communities we are encouraged to mine.

Exploitation is a chain that the wealthy and powerful find themselves at one end of.

It is our politicians, the same that failed to regulate the banks, the same that profited during a crash that left people homeless. As they try to patch up the failing fabric of communities destroyed by successively punitive policies, relying on this notion of Big Society, the shifting of responsibility but without the shifting of financial power.

And so the politicians have exploited arts funding, which in turn exploits artist, who in turn exploit the communities that they work in.

And that exploitation is frequently hidden behind a language, a language of inclusiveness.

The language of Big Society.

Representation and agency as a cloak for exploitation.

---

[SKINNINGROVE]

I'm still stood there looking down the ventilation shaft.

I'm there to make art, but I'm aware of why. And I don't want to exploit anyone, I don't think any artist does. Mostly, I think artists want to make art.

But that's not the mine we work in anymore.

And the sound of over a decade of Big Society plays through the vent like a flute. It plays a whimsical tune of austerity fixed by thin air and good will.

I listen to the lyrics, and I can't quite hear them, but the chorus sounds like "It's not about hugging a hoodie, it's about being embraced by a community".

References

[1] D. Cameron, The Big Society Speech, July 2010 (https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/big-society-speech)

[2] S. Wollaston, Artist in Residence: Sex Clinic review, (The Guardian, 22/07/2018) (https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/jul/22/artist-in-residence-sex-clinic-review-very-informative-and-not-just-about-down-there)

[3] Neon, NEF, Framewporks Institute and PIRC, Framing The Economy, February 2018 (https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/Framing-the-Economy-NEON-NEF-FrameWorks-PIRC.pdf)

[4] W. McMahon, The Politics of Anti-social Behaviour, April 2006 (http://www.crimeandsociety.org.uk/articles/polantisocial.html)

[5] D. Cameron, Speech to the Centre for Social Justice, London, 2006 (http://www.britishpoliticalspeech.org/speech-archive.htm?speech=318)

[6] S.Cattan, C. Farquharson, IFS.org.uk, August 2021 (https://ifs.org.uk/news/their-peak-sure-start-centres-prevented-13000-hospitalisations-year-among-11-15-year-olds)

[7] Community Care, ‘Momentum for change’ to tackle profession’s staffing ‘crisis, May 2023 (https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2023/05/12/momentum-for-change-to-tackle-professions-staffing-crisis-says-social-work-england-lead/)

[8] C. Killip (https://www.chriskillip.com/skinningrove)

[9] M. Almereyda, Skinningrove, 2013 (Getty Museum, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ENzA-vIwAgQ)

Adam York Gregory March 2024

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.