Six Questions with Hannah Leighton-Boyce and Uma Breakdown

Axis Fellows Hannah Leighton-Boyce and Uma Breakdown in conversation

Hannah Leighton-Boyce and Uma Breakdown

Hannah Leighton-Boyce:

How have things have been going since our final fellowship session in April?

Uma Breakdown:

Good thanks! It’s been the final months of my residency at The National Glass Centre in Sunderland so I've been spending a lot of my time there, mostly working in ceramic. It's been really good to have this space to focus on exploring processes and figuring out what ways of working with this material fit with how I do stuff. I made lots of things, none of them for any future show, and that's incredibly liberating!

HLB:

I loved seeing some of these experiments and developments of your work during the fellowship! I was thinking back to our collaborative workshop at the start of the fellowship around ghost objects and unfinished business - an object of fascination/interest which has never satisfactorily been accounted for or lingered with you - and I was trying to recall what I had shared so I looked in up our session notes and it reminded me that it was an excerpt of a piece of writing that was never resolved/ interrupted by my health in 2022 and amazingly, a few days ago (at the time of writing), I read this still unfinished business (but now with a title) at ‘The same deep water as you’ (a dreamy night of live performance and video work by 16 artists, programmed by the artist duo ‘Rowlands Leaving’ at PINK in Stockport). I hadn’t realised I had done this, brought it further to being resolved, and it made me think about whether it needs to be. I like now that it might be ongoing or have different iterations, I also like the fact that performance or perhaps a more accurate description is a live reading allows me to lean into this further. And this is a very long and winding way into a question about ‘resolving things’, whether things need to be, and if thinking back to the work you shared in that first session, ‘Criminal Child’ how you now feel in relation to it now, has that changed?...

UB:

That's fantastic! It's so wonderful to hear that the writing you shared not only got picked up again, but without it being this conscious thing! I’ve not thought about Genet much recently, but that text is under so much of what I do that it might be more of a thing I’ve dealt with in a structural way. A large amount of it is about collective language, an argot for a group that is almost always ‘outside’ in some ways. I think this is ultimately how I think about my work. I want it to be welcoming to all, but it's particularly addressed to what I think of as my community, and for whom I hope it has a more intimate feeling.

I relate with what you're saying about live readings and performance as a context where things don't need to be resolved. It's one of the best things about that kind of work that it's always a rendition, always a different version. Like presenting something ‘live’ is still functionally the same as practicing it in your studio because you learn to do it a little differently, get a bit fed up with some parts that feel stale, or just make mistakes.

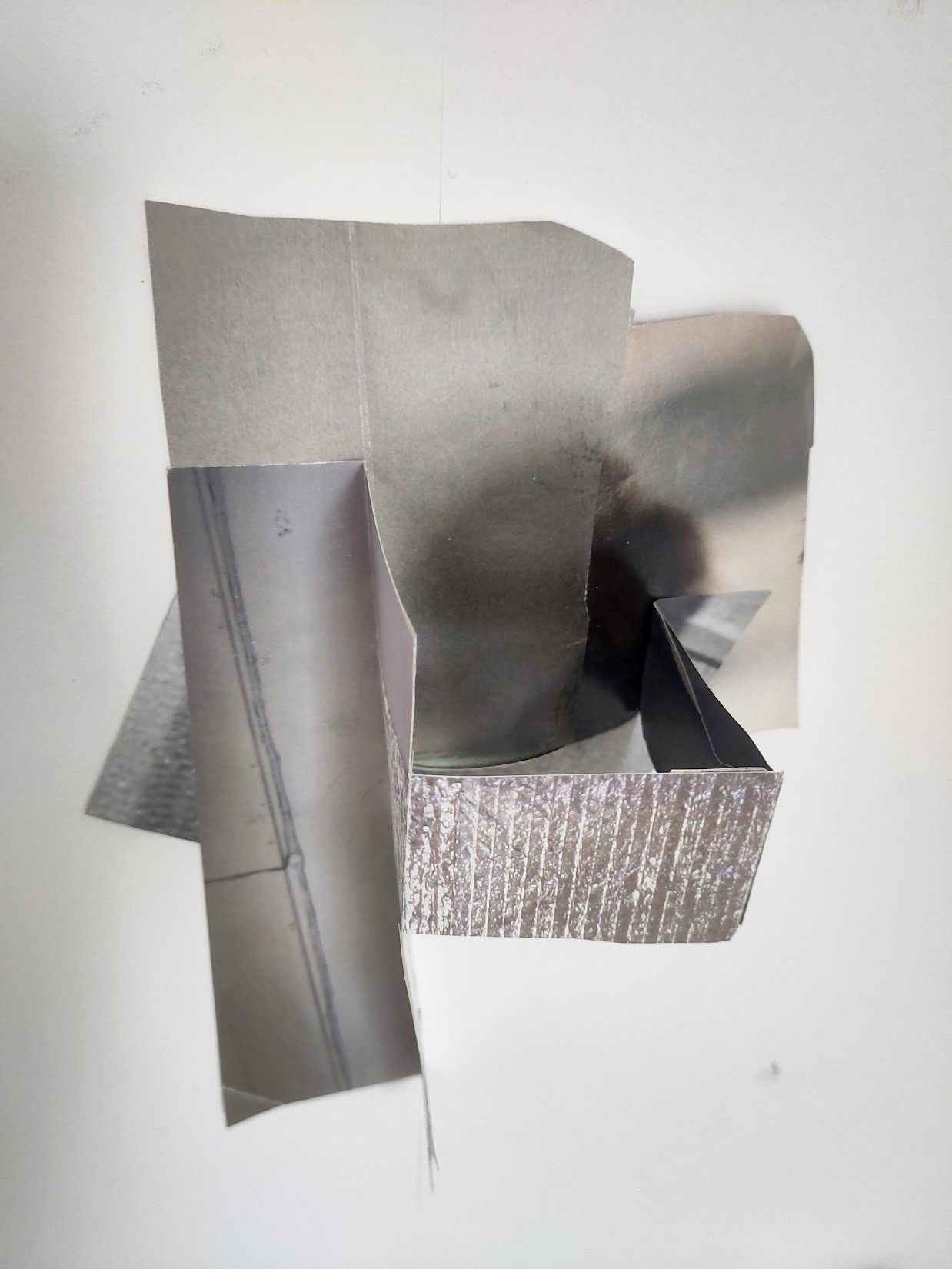

Hannah Leighton-Boyce, studio documentation 2025

HLB:

…Maybe some of our workshop questions might be helpful here too -

How does it sit in relation to your practice, close, far, above, below, in line of sight, hidden?

UB:

I think the answer is “under”. It's sunk down to the level of ethics and desire.

HLB:

What is your position to the object/work now?

UB:

I think it's a general guiding text. It's a message of refusal, both Genet’s own refusal to play the part the state set him, and the refusal of the kids in the prison he talks about. You don’t have to go along with the vile organs of power, you can have your own ethics and politics, and there is something beautiful in just refusing. I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. Living and working at the edge of England, where Glasgow, Dundee and Edinburgh are closer than London, I can’t help but contrast the art community culture of Scotland to England. During the 2010s when I was living in London there was a very active movement to boycott art organisations with direct ties to weapons manufacture and the violent occupation of Palestine, with a focus on the Zabludowicz Art Trust. While we managed to keep this boycott visible throughout the 2014 Gaza War, so many artists that I knew decided to cross that picket. Decided that they would not refuse those vile organs of power, and that the game as it was should be played, rather than denied. I can’t help contrast that to the culture in Scotland now, where giving no quarter, artists have forced change on a number of institutions, changing board positions and sponsorships. At the time of writing, Art Workers for Palestine Scotland is working tirelessly to change CCA Glasgow. What has been particularly beautiful to see is that, when CCA called in the police on protestors for organising a peaceful sit-in, AW4PS refused to back down and efforts have redoubled, with demands now including the removal of the board members who helped coordinate that police response. There’s no slow death of allowing an ethical position to be withered away with compromise and fatigue, while active individuals with names hide behind an organisation's name and the banality of “how things are done”. This feels like the joy of the Criminal Child to me.

HLB:

I wondered if you could say more about working in parts, fragments, and perhaps dismemberment? I feel it’s another shared interest of ours, although it shows up in different ways within our work

UB:

There’s a big, overarching strategy in my practice where I’ve realised that I make my best work when I’m able to take risks. Or rather, I don't make good work when I’m anxious, and tend to sabotage things. So I try to make things as non-stressful as possible, which means I work in ways where if something goes wrong, or don’t like what something comes out like, it doesn't matter because I can endlessly do it over. So when I draw, cutting out the bits I like, pasting over bits that have gone wrong, and just making everything in little fragments to re-assemble has become part of the workflow. There’s never a point when the work is not recoverable. I draw a lot of figures in my work, and I’ve taken to drawing them as a bunch of dismembered body parts and articles of clothing, often with variants of limbs so I have even more room to assemble them in the way I want. I do similar things with all the other stuff I make, everything is produced in quick fragments which can easily be swapped out if they aren’t right. When I do a show, I turn up with boxes of these small things which are then built together into something big, no single part is essential.

As part of my mentoring for this fellowship, I met with Michael Hill from Temple Bar in Dublin and he proposed that the dismembered thing was not just a strategy for things like drawing and sculpture, but a central philosophy for the work. That it is part of what my work is about. I obviously work around horror and had literally been researching Christian martyrs when Michael and I were talking, but I’d never really made the connection before. That the dismembered body could be a model for what I was doing, similar to Hobbes’ Leviathan, or Bataille's Acephale man. So, I’m currently, gently, trying to unpick this a little in my work. Trying to understand the repeated motifs of floating heads and hands, and the writing that is so frequently hyper focused on very localised bodily sensation and the moments when parts of your body no longer feel like they are part of you. It's early days, but It's been a really really helpful guiding premise.

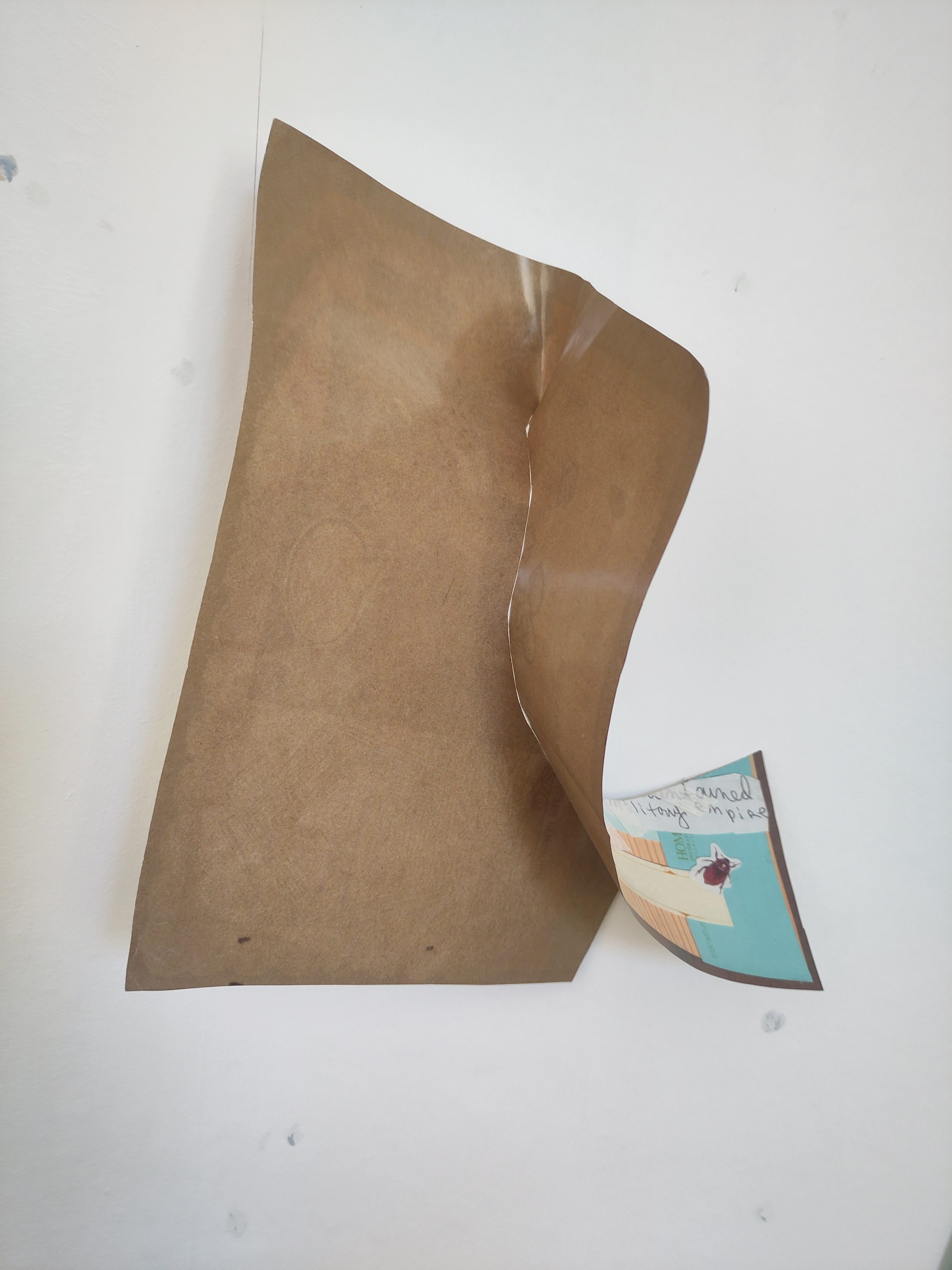

Uma Breakdown, studio documentation 2025

HLB:

And linking to this another interest we share is around notions of repair and appropriation and re-appropriation and what this means for you?

UB:

I’ve talked a little about repair above, but I'd add that for me repair is the “natural state”, everything is in the process of repair. I think this probably comes from being disabled, and working in care work for so long, but I find a lot of optimism in thinking of the world like this. Everything is already broken, and it's being repaired. There’s no state of “fixed” and the repair isn’t trying to turn back the clock to some prior perfect moment, but everything is “in progress”. Again, it removes the anxiety for me, and I have almost a reactive response to art that has glossy sheen of perfection, that says that it is untouched and unblemished. I feel much safer with art that shows signs of its own repair, that shows scars and resilience.

Appropriation is a little different. I like language, and patterns, which is what language is made of. I work with genres, particularly Gothic Horror, because it has all these patterns and motifs, and they can be built with, or broken. You can still say anything you want with this language, but it has an overall tone that kind of sets the context to being about the things I'm most interested in, namely things that are about sensation, and things that are beyond description.

Repair seems very important to your work. I've been thinking about how repair often has one of more directions involved, as in it's going somewhere, such as going somewhere as close as possible to where it came from, or going away from the events that caused it to need repair, or going towards something else that in combination with itself will make it stronger or more stable. Are there directions in your work?

HLB:

In terms of direction this has varied, it’s probably less about one direction and more about a field of movement, rather than returning to something close to what was, it’s more about something evolving, renewing, and replenishing. I’m sure this interest partly stems from developing a chronic condition as a teenager, but I also grew up in a DIY fix-it household, my playground was a building site so I became used to everything being in process in that way too and I often made things with scraps of materials. Later, when I was well enough to go back to studying, I moved towards textiles and one of my first opportunities after graduation was a residency where I had access to an incredible archive of 18th century darning samplers and drawing analogies with living with a condition that is for the large part invisible to others. The samplers were fascinating to see different ways of repairing fabric which were celebrated as embellishment and reinforcement rather than something to hide or returning it to its origin, how it looked before.

I recalled these again when I started to weave paper as a process of joining within collage instead of perhaps tape or glue. I had been thinking about grafting as a process of joining and transforming or becoming and then, when I was in hospital receiving cancer treatment, I found I was willing my cells to do the same. The weaving process is very involved and it opened up a space for me to escape and discover when I wasn’t allowed out of a hospital room for several weeks - the internal workings of my cells and neurological processing of my body receiving treatment met the external process of weaving and they became somatically entwined. I see strength in the work I made in hospital, partly because they weren’t trying to be works and more just meeting my necessity to be occupied with making and transforming material. I’m still playing and enjoying seeing where my studio explorations take me and trying to stay with a feeling of ‘just enough’.

Hannah Leighton-Boyce, studio documentation 2025

UB:

Is damage important to your practice and what does it do that's different from repair (if anything)?

HLB:

In some ways it is - the process damage (or dying), repair and renewal - they’re part of the same fragility process of existence. Sometimes I explore this through material choices and decisions around their application or display that means they remain susceptible to environmental changes and touch, or structures that are propped or leaning and could collapse - I’m interested when something feels responsive and contains an aliveness. I was about to say that, in my collages, things feel a bit different, but I think it is all a search for this same connection or expression but through different times, materials, and experiences.

I recently reconfigured a work for a group show using large sheets of discarded waxed paper that have been used in a factory as an interstice between the damp clay tile as it dries and the wooden board that it rests upon. The slightness of this paper holds an important function in its ability to slip, to be responsive and move

with the contraction of the heavy clay tile as it dries. This prevents it from cracking and the contact within this drying action of the contracting clay, and its impression is held within the wax paper. There is this moment in an action or contact within an event that I am interested in and how an object, material, and bodies can hold the memory of this. The meeting points and overlaps of different surfaces, images and textures within the collages connect with this expression of movement or gesture within the event too.

I was thinking about framing and showing work in a formal gallery or museum context and how you shared some of the experimentation with this in your current work. Is this exploration also linked to repair…how something is framed physically, contextually, culturally?

UB:

Framing is both a quite banal part of my work and something that's probably quite deep if I ever get round to looking at it properly! As mentioned above, I work in quite rough scrappy ways. I work with cheap materials so there's never a sense that if I mess this up, I won't be able to afford to try it again. So I have all these drawings which are really important to me, but I worry they can't really stand up on their own in a gallery space. I also don’t want to just use the language of the museum. My long time remote studio neighbour, Johanna Hedva, a couple of years ago said something along the lines of “the museum brings your weird work in to their space because its makes them look good, and then it can't help also make your work look bad in contrast, you need to make your work look good, and them look bad!” How I’ve interpreted this is bound up in that language of the museum, the invisible or pretend invisible codes of things like plinths, frames, lighting, spacing, tone etc. And my strategy has been; I really love the work I make, I care a great deal for it, I will therefore treat it with a huge amount of care even though it's these silly little collages of goblins. So everything about how the work is presented is very hands on and very considered. Nothing is presented using any of the museum’s language, with plinths or frames that are not specifically made for it, or take a form that exists prior to those drawings or sculptures. And because I do a lot of drawing, framing is a big thing. What can mark the edges of the drawing and also keep it safe and in the right place? It's something I’ve been working on for a few years now. I think a lot of the ceramic things I’m working on are actually leading up to a bit of a system for this.

Uma Breakdown, studio documentation 2025

HLB:

We chatted a little about diagrams and design processes at the start of the fellowship, but I’ve taken this note of ‘experimenting with different workflows until something sticks’ from our session notes and it’s something that is often on my mind too. I was wondering how this is going?

UB:

Oh god. I wish I was organised enough that I could have a system that lasts. Every time I switch back to a way of working like drawing or writing or animation, I yet again have to work out from scratch a new process to do this. I think I must learn stuff between all of these attempts, so it's not truly “from scratch”, but it's very much the case that when I pick up a pen, and start using the system of working from the last time, it will produce nothing but garbage. So I guess that's the system, the old system goes off, and the first (and probably second and third) thing made is always bad, until I loosen up enough to try something completely new!

I watch a lot of television, and I'm currently very into a gritty medical drama, I think mostly because it's so satisfying to watch all these systems (the team, the hospital, the city, the mass of patients, the systems of a body) working together and generating outcomes. Are there systems in your practice, and do you think about any part of those systems as "work"? (also what tv are you into?)

HLB:

That sounds really good! I’m not watching much at the moment and I could do with some suggestions for both tv and viewing platforms as I’ve just lost access to Box of Broadcasts and I’m really missing their archive. In general, I have a terrible memory for remembering any detail in what I have watched, and this is not tv, but I recently watched Maryam Tafakory’s ‘Irani Bag’ which a friend recommended to me. I imagine you have seen it but, in case you haven’t, it’s a beautiful and tender arrangement of clips taken from Iranian films that demonstrate the presence of absence (or prohibition) of touch in Iranian culture and the use (in film) of the bag as a prosthetic extension, mediator, and threshold of and between bodies. I now wish to watch lots of Iranian cinema. Ha! I went straight to the TV part of your question and forgot the first part…systems. I’m not sure, I'm always trying things too but I don’t think they are regular enough to call a system. Actually, well, maybe they are - a big part of my being able to make work is my health the care and maintenance work around living with chronic health and cancer aftercare treatment - so elements of my system would be hospital appointments, medication, as well as swimming, mediation, and yoga, seeing/experiencing good stuff, resting, laughing, seeing friends. It’s a matter of regularly checking in with my body and the whole system that is daily life to see when things are working well or otherwise, usually it takes a bit of a wobble to see if something needs adjustment or is missing! In terms of the studio and making, I think little and often in the studio works for me and keeps me tapped in but it’s the focused period that a residency offers where most of the movement happens and the majority of work is made.

Hannah Leighton-Boyce, studio documentation 2025

UB:

In 1987 Rem Koolhaas proposed the Strategy of the Void, an approach to architecture that centres space and the unbuilt, as the “enabling fields” of potential, and it's something I've thought about a few times when looking at your paper works. What is the role of voids for you in your practice?

HLB:

Thanks for sharing this, I'd not come across their work, but I relate to this idea or proposition of voids being ‘enabling fields’ of potential…

It makes me think about meditation. I have this long-term interest in gaps, absences, and the spaces between, in the past these have perhaps contained something missing or lacking but also very connected to the body. Within my work, this void or space or field has surfaced through material interactions that open up the sensory and embodied in the making and viewing experience.

Currently, these feel more like places to explore, access, get into and between, a position to occupy and work from. It’s also about the edges of these places, and that feels connected to living with a health condition that is disabling, it’s not necessarily or always a space of comfort or discomfort but equally it can be. It can be about ease of movement, or not, or perhaps accessed by a slippage or a fall, currently I think I am peeling at the edge of a sticker and seeing what happens - for me, it’s a little of what John Berger describes in the Shape of a Pocket as ‘seeing between two frames […] the interstices between different sets of the visible’

In my paper and collage works, these physical voids and absences come about through selecting and removing information, a letting go and loosening from what the image meant, to possibilities of what else these might contain. I make these decisions quickly, they are more of a tuning in, sensing and instinctive, of seeing them in their thingness. So, I’m then working with these piles of fragments, holes, primal cuts, shapes that no longer have a particular orientation and the points where they overlap.

UB:

I know you work across different mediums and processes, how do you know which idea or interest or image will wind up within say an object as opposed to a text or performance?

HLB:

It’s something I am always working on! As is often the case, usually it’s the first thought that I return to but I’ve found that collage helps me get closer to this as it’s a space where I feel and know my decisions, they are clear, instinctive, and I don’t tend to question them and that’s something I am trying to bring through into how I work in other materials and processes. Collage just is until it’s not and then I need to do something else, which reminds me of something Sophie Jung said to me during a tutorial, it was right at the end of a conversation, and it has stuck with me, ‘Surround yourself with things that don’t make sense’.

I’d love to hear more about how things are going for your show next year?

Uma Breakdown, studio documentation 2025

UB:

Good! I’ve been working on a bunch of other things. Like I just handed in an animation that's going to be shown as part of Berwick Film and Media Arts Festival, and I recently filed an academic article on Luce Irigaray and will be presenting some other stuff at the Irigaray Circle in a few weeks. I’m also writing a new performance for an event at Raven Row and getting ready for a research fellowship at Henry Moore Foundation. All this stuff is doubling up as ways of thinking through, or developing skills for the solo show at God’s House Tower next year. Again, a lot of the things I’ve been doing in the clay room will also be leading to that. Particularly around the issue of frames, but also I’m making things that can be used in different ways to build up the show, pieces that can be used to build different structures depending on need. Like a tool kit. I guess that's what I've been doing over all, building up the tool kit for the show!

Likewise, I'd really like to know what you’re working on at the moment and how these different things you've been exploring might be crossing over!

HLB:

It all feels like things are beginning again after having a few years where I had to prioritise my health, things feel more balanced now and that feels exciting! I want to keep things playful and explorative, seeing how my research might become more embedded into my work and spend as much time as I can in the studio. I also want to keep working on all the things that are supporting me to stay as well and healthy as possible, being part of the fellowship was a big part of this. I recently heard that I’m part of the Syllabus VIII cohort which feels like a brilliant way for me to continue to build on what the Axis fellowship has enabled but in a slightly different way. We're currently planning for our next gathering at PS2 in Belfast, I’m excited to see how these relationships might grow and develop over the next 10 months. Then, in September I’m beginning a ‘Women in Print’ residency at Artlab and Uclan University, I’m really looking forward to being absorbed into the community of the print room and printmaking again!

Artists

Tags, Topics, Artforms, Themes and Contexts, Formats

Share this article

Helping Artists Keep Going

Axis is an artist-led charity supporting contemporary visual artists with resources, connection, and visibility.